Sports performance may seem like a strange topic to include in this discussion. After all, as I explained in the main text, when we talk about race and genetics, we are usually concerned with fundamental characteristics, such as intelligence or aggression, and not how far a particular person can throw a ball, or how high they can jump. Nonetheless, sports are such a popular and visible part of society, that they function as a kind of open field, where erroneous beliefs and racist myths are projected and disseminated. There are also some aspects of sports performance that cry out for explanation, and can potentially shed light on a larger discussion of race and genetics.

Several years ago, one of my students asked me whether or not it was true that black athletes “add muscle mass” faster than white athletes. This student was intelligent, sincere, and not racist. He was simply trying to explain the observation that black athletes appear to be more successful than white athletes in some sports. He assumed, falsely though reasonably, that black athletes are different, that their bodies or brains make them particularly suited to competition.

I answered that, while one individual may well develop muscle mass faster than another in response to training, there is no evidence that black athletes as a group add muscle mass faster than white athletes. Nor is there any truth to other common theories that explain the success of black athletes, such as notion that black athletes have higher levels of testosterone, making them more competitive and aggressive, or that African Americans, largely descendant from slaves, represent the “fittest of the fit,” the strongest individuals who survived the brutality of the slave trade in the past, and therefore dominate sports today.

Why, then, are black athletes disproportionately successful in some sports? I will try to answer this question using the same approach I have followed throughout this website, namely, by arguing that there is no basis to distinguish human races, but that our history has produced unique variation that is evident in several areas, including sports performance.

To begin with, we must determine that black athletes are more successful than white athletes. In North America, black athletes dominate two of the most popular professional sports, basketball and football. Baseball is more diverse, and white and Latino athletes enjoy considerable success. If we consider other sports that require similar skills, such as rugby, lacrosse, or volleyball, we find a surprising lack of black athletes. And that only involves field sports with teams and a ball. If we consider sports such as swimming, gymnastics, tennis, golf, rowing or sailing, a small number of notable exceptions notwithstanding, black athletes are hardly represented at all.

If we expand our view to include international sports, the patterns change. European basketball is played mostly by white athletes. Soccer, the most popular professional sport in the world, is quite diverse, and it would not be fair to say that black athletes dominate, although they may appear to in countries that are predominantly white. Cycling is almost entirely white. For over one-hundred years, the winners of the Tour de France, the flagship event of professional road cycling, second only to the Olympics and World Cup soccer in numbers of viewers, have been predominantly white. There have been a handful of competitive Latino cyclists, fewer Asian cyclists, and still fewer black cyclists. Recently, an African cyclist won the Tour de France for the first time—but he is white, and grew up in the United Kingdom. Sports popular in India and Pakistan, such as cricket, and sports popular in Asia, such as table tennis and badminton, are dominated, not surprisingly, by people from these regions.

If we consider winter sports, the patterns change again. Black athletes are almost completely absent from sports such as ice hockey, and various ski disciplines. Finally, if we consider female sports, the patterns are similar, with some variation. For example, the most successful male soccer teams are from Brazil, while the most successful female soccer teams are from North America.

This survey demonstrates that black athletes are not necessarily more successful than white athletes, or any other athletes, in all sports all of the time. It should be clear that sports success is determined largely by culture. Some important factors include: history, tradition, income, poverty, social class, economic incentives, marketing, climate, geography, role models, infrastructure, including physical resources and human resources, and, in some cases, political forces. These factors explain why black athletes participate in sports such as football and basketball, while white athletes participate in sports like golf and sailing (these sports are associated with income and social class). They also explain why black athletes are absent from winter sports (countries with large black populations do not have cold winters), why black athletes have not won the Tour de France (countries with large black populations do not have the required infrastructure), and why black athletes do not dominate sports such as cricket or table tennis (these sports are not popular in countries with large black populations). Very few people would disagree with these assertions.

At the same time, I don’t think it’s enough to say, “Success in sports is determined only by culture.” This is not a satisfactory explanation, and leads to more doubt than certainty. Can culture really explain sports success? Are black athletes really the same as white athletes?

To answer these questions, we need to find a sport that 1) is popular around the world, 2) is practiced by many people regardless of history, nationality, income, and social class, and 3) requires very little infrastructure. Fortunately, a strong candidate exists: running. Of course running is influenced by culture, but much less so than other sports. Therefore, it provides an ideal context to compare the performance of different athletes.

In the past, famous runners came from all over the world, including the Americas, Africa, Europe, the Middle East, India and Asia. There were legendary Andean distance runners, British milers, Moroccan middle distance record holders, Indian sprinters, and Japanese marathoners. However, since the late 1980s and early 1990s, black athletes have dominated running events at major international competitions, such as the World Championships and the Olympics.

Sprinting events, like the one hundred meter dash, are usually won by large powerful athletes from West African nations, such as Cameroon or the Ivory Coast, or from former colonies populated by slaves from these nations, such as Jamaica and the United States. Long distance events, like the marathon, are usually won by small light athletes from East African countries, such as Kenya and Ethiopia. Middle distance events are won by athletes from throughout Africa, especially North Africa. This is true of both male and female competitions. Occasionally, white athletes reach the finals, but the winners are almost always black.

The success of black runners demands explanation. Culture must play some role, even a large role. Cultural factors often work in circular fashion, that is, as runners gain recognition and wealth, their countries gradually develop support systems and infrastructure, and more successful athletes emerge. However, these factors cannot fully explain the overwhelming success of black runners. A satisfactory explanation must go further.

The answer may be related to processes I discussed above, namely, genetic bottlenecks, and the founder effect. Recall that the humans who left Africa about 65,000 years ago were a sub-population of a larger ancestral group. This migration, and all subsequent migrations, represent a series of founder events. Humans who left Africa carried with them only a fraction of the genetic diversity that remained behind. Alternatively, humans who remained in Africa had more genetic diversity that those who left.

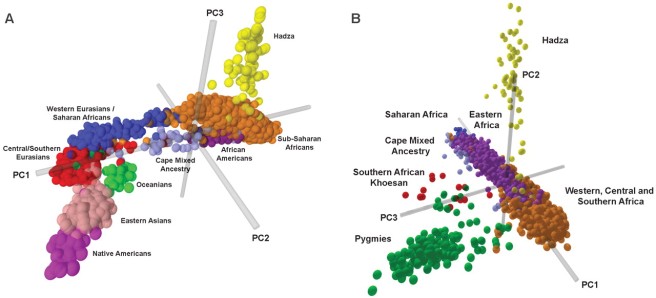

The American biologist Sarah Tishkoff and her colleagues examined over one thousand genetic markers from 121 African populations, four African American populations, and 60 non-African populations. The figure below shows the results of their analysis.

The axes (gray lines) represents different statistical variables. The data (colored spheres) are distributed along the axes, and provide a three-dimensional representation of genetic distance. If the spheres are farther apart, there is greater genetic distance between the populations, and if the spheres are closer together, there is less genetic distance between the populations.

In the first picture (A) you can see that the genetic distance between populations in Africa, such as the Hazda and Saharan Africans, is greater than the genetic distance between populations in the rest of the world, such as Eurasians and Oceanians. In the second picture (B) you can see the genetic diversity in Africa. For example, Hazda and Pygmy populations, and some members Saharan African and Southern African populations, are separated by substantial genetic distance.

This study is noteworthy because, historically, Africans were treated as a relatively homogeneous group. We can now see that there is far more genetic diversity in Africa than anywhere else in the world.

Figure 13. Human genetic variation in Africa. Tischkoff et al. 2009.

Figure 13. Human genetic variation in Africa. Tischkoff et al. 2009.

Because Africa has greater genetic diversity than anywhere else in the world, we expect to find the fastest sprinters and the fastest marathon runners there. For the same reason, we also expect to find the slowest sprinters and the slowest marathon runners. Imagine the results if a West Africa runner competed in the marathon, or an East African runner competed in the one hundred meter dash. Following the same line of reasoning, we expect to find the extremes of most characteristics in Africa. We can return once again to height. Do we find the tallest and shortest people in Africa? Because height has an environmental component, it’s difficult to compare countries directly, but there are definitely very tall and very short populations in Africa, for example, the Massai, an extremely tall and slender people from Kenya, and the Mbuti, one of several indigenous groups of pygmies from Central Africa.

This is one explanation for the disproportionate success of black athletes in some sports. It acknowledges that success is determined in large part by culture, but asserts that there must be a genetic component as well. It offers a plausible mechanism to explain genetic variation, and it is supported by evidence. Furthermore, it does not support any commonly held racist beliefs. At the very least, this is the kind of explanation that we need to explore to understand human variation.