I would now like to turn my attention to an extremely important question. In many ways, it constitutes the second chapter of any discussion of race and genetics, and I usually present it to my students only after we have discussed the fundamentals in some detail.

If we accept that there are no fundamental differences between people around the world, how can we explain the last five hundred years of history? Why have some people succeeded while others have not? Why is there such an enormous disparity in the global distribution of power and wealth? Why didn’t Inca conquistadors, wearing helmets made of gold, sail across the Pacific, and lay siege to the Catholic citadels of Portugal and Spain? Why didn’t Zulu warriors, riding zebras or elephants, conquer Europe, and establish a white slave trade? Why didn’t Chinese or Indian vessels sail into British ports, and develop colonial trading outposts?

The answers to these questions have traditionally been racist answers, namely, that white people have succeeded because they are superior, genetically, biologically, culturally, and so on. We now have more informed answers, based on geography.

A full treatment of this subject can be found in Jared Diamond’s remarkable book, Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. Diamond’s book is triumph of reasoning and research, backed up extensive evidence. I will not do justice to his work in this short space, but I will try to sketch the rough outlines.

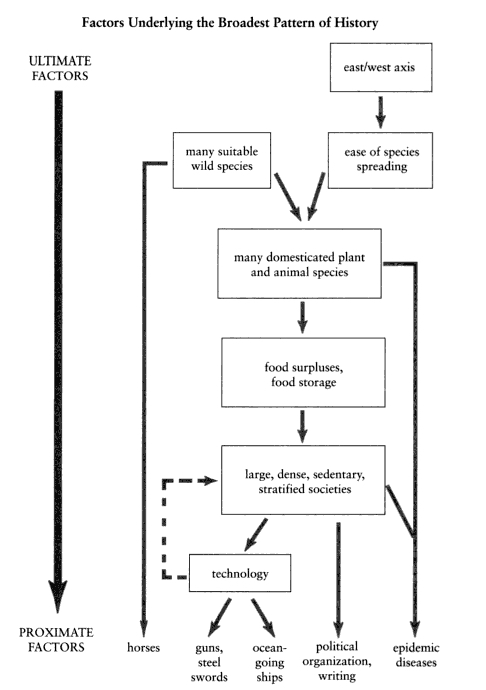

The figure below shows several factors that contributed to the success of particular societies around the world, from approximately the time of the agricultural revolution, to the present. Although the figure is not strictly a timeline, you can think of top as the past, and the bottom as the present. More distant factors (ultimate factors) are shown above, and more recent factors (proximate factors) are shown below, with arrows defining the causal relationships between them.

In summary, the east-west orientation of the long axis of Eurasia created a vast region with a stable and hospitable climate, and numerous plant and animal species available for domestication. This contributed to the agricultural revolution, food surpluses, and the ability to sustain large dense societies. Once these societies developed, opportunities for trade, communication, and the rapid spread of technology followed. Diseases were also able to move freely, and populations resistant to those diseases emerged and thrived. European societies were therefore able to develop technology that allowed them to conquer other societies, as well as the economic, political and social structures that impelled them to do so, and the diseases they carried with them, toward which people from other continents had no defense. As the title of the book suggests, guns, germs and steel largely determined the fates of societies, and these factors themselves were largely determined by environmental factors.

Figure 1. Factors underlying the broadest pattern of history. Diamond, Jared, 1997. Guns, Germs, and Steel, The Fates of Human Societies. W. W. Norton and Company, Inc., New York, NY.

That’s the basic theory of Guns, Germs, and Steel. It seems hard to believe that such a simple idea could explain human history, but Diamond marshals an extraordinary number of examples to support his arguments. For example, consider the number of plant species available for domestication around the world. Diamond examines large-seeded grass species, such as wheat and rice, the foundation of agrarian societies. He shows that, at the time of the agricultural revolution, there were 39 large-seeded grass species in Eurasia, 4 in Sub-Saharan Africa, 11 in the Americas, and only 2 in Australia.

Likewise, Diamond examines the large mammals, such as horses and cattle, which were used by early societies for transportation, traction, war, trade, and so on. As above, Eurasia had a great many more available large mammal species compared to other continents. 13 mammals were domesticated in Eurasia, only one in the Americas, and none in Sub-Saharan Africa and Australia. This information is summarized in the tables below. While the global distribution of plants and animals is very different today, because of large-scale migration, it’s clear that early societies in Eurasia enjoyed a distinct advantage relative to their counterparts on other continents.

Large-seeded grass species available for domestication

| Geographical area | Number of large-seeded grass species |

| Eurasia | 39 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 4 |

| Americas | 11 |

| Australia | 2 |

Large mammals available for domestication

| Geographical area | Possible mammals | Domesticated mammals |

| Eurasia | 72 | 13 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 51 | 0 |

| The Americas | 24 | 1 |

| Australia | 1 | 0 |

Table 1. Large-seeded grass species, and large mammals, available for domestication at the time of the agricultural revolution. Diamond, Jared, 1997. Guns, Germs, and Steel, The Fates of Human Societies. W. W. Norton and Company, Inc., New York, NY.

Guns, Germs, and Steel has garnered a great deal of praise, but it has also attracted its share of criticism. I think it’s worthwhile to examine the most common criticism of Guns, Germs, and Steel, if only to better understand Diamond’s work.

The most common criticism of Guns, Germs, and Steel involves the truth or one or another specific point. In a book so broad and deep, this is hardly surprising, and perhaps inevitable. Researchers in different fields claim that Diamond ignored the fact that native people in the Americas might have begun to domesticate plants and herbs, that he discounted the potential nutritive value of root crops such as yams and taro, that he misrepresented the relative ease with which plant and animal species spread throughout Eurasia, that he downplayed the possibility that species migrated along north-south corridors, that he overstated the importance of domesticated animals, and so on.

These points challenge Diamond’s ultimate factors, and therefore weaken his argument. Some may have merit, however, even taken together, I do not think that they constitute a substantive refutation of his theory. On the contrary, for the most part they seem trivial. I believe that much of this criticism is simply intellectual jealousy. Academics often object when others trespass in their areas of expertise, or do not pay sufficient homage to the literature. In any case, critics have offered no comprehensive alternative theories, thus Diamond’s work remains relevant and powerful.

A second criticism of Guns, Germs, and Steel is that it is overly Eurocentric. This accusation takes various forms, however, in general, people claim that Diamond focuses exclusively on the success of Western Europe, and disregards the history, experience, and accomplishments of other societies. It’s difficult for me to appreciate this criticism, because the dominance of the Western Europe is precisely the outstanding fact that Diamond is trying to explain. It makes perfect sense that he spends time elaborating this process, although, I would say, he focuses equal or greater attention a vast number of different societies around the world.

A third criticism of Guns, Germs, and Steel is that it is overly deterministic. According to this view, Diamond claims that the environment determined human history in absolute terms, and that events that shaped civilization could not possibly have occurred differently. Above, I used the word determined in much this way: guns, germs and steel determined the fates of societies, these factors were themselves determined by geography. This use of determined is a conventional way to express causality, but Diamond would be the first to argue, and I would be the first to agree, that the environment only determined preliminary conditions, and that exactly how societies developed involved a considerable number of other factors, which may or may not have had anything to do with geography. In this sense, the environment determined the potential for development, and not precise course of human history.

The idea of determinism lies at the heart of two related criticisms of Guns, Germs, and Steel. First, some people believe that Diamond justifies or supports the behavior of Western Europeans. For the sake of argument, assume that environmental factors did precisely determine human history. If this were true, it would absolve humans of responsibility for their actions. The environment made Western Europeans set forth from their homelands and colonize distant continents. The environment made North Americans enslave Africans. Colonialists and slave masters had no say in the matter, and only fulfilled their destiny, determined by the stable climate, free flowing rivers, fertile soils, and rich flora and fauna of Eurasia. Or, alternatively, the native people of the Americas, Africa, and Australia, were powerless to defend themselves, and had no other choice but to succumb to their oppressors.

This frees Western Europeans and North Americans from any feelings of guilt, and allows them to avoid acknowledging their past. It denies the agency of people colonized and enslaved, and precludes their potential to defend themselves, or pursue alternative outcomes. Thus, it both absolves the perpetrators and enfeebles the victims. We could call this the “liberal argument against determinism.”

Others interpret Guns, Germs, and Steel in a nearly opposite manner. They believe that Diamond fails to hold less successful societies responsible for their own failure. Again, for the sake of argument, assume that environmental factors did precisely determine human history. If so, the choices, decisions, mistakes, and deficiencies (including, perhaps, biological deficiencies) of individuals and societies, are irrelevant. In simple terms, the fact that some societies have failed to thrive is not their fault.

This is difficult to accept for people who believe strongly in personal responsibility, and do not readily admit that external factors often play an important part in success and failure. They rather believe that some societies have succeeded because they are superior, or because people from these regions made good decisions, worked hard, or seized the opportunities that were presented to them, while other societies have failed because they are inferior, or because people from these regions made poor decisions, did not work hard, failed to capitalize on the opportunities presented to them, and so on. We could call this the “conservative argument against determinism.”

As I explained, I do not believe that Guns, Germs, and Steel is deterministic in an absolute sense, and so I do not believe that either of these narratives is true. In the first case, Diamond does not absolve any group from responsibility for their actions, nor deny agency to others. Instead, he confronts and chronicles the injustice of human history as fairly and objectively as possible.

In the second case, the whole point of Guns, Germs, and Steel is to offer an environmental explanation of human history not based on the superiority of a particular group of people and the inferiority of others. That’s the reason that I have taken the time to explain Diamond’s work in my discussion of race and genetics—because he shares the view that there are no fundamental differences between humans around the world.

A final response to Guns, Germs, and Steel is a question, one that my students frequently ask, and that many readers doubtless ask as well. If we assume that the broad middle swath of Eurasia, lying along the same east-west long axis, shared roughly the same stable and hospitable climate, and great number of plant and animal species available for domestication, why did Western Europe ultimately rise to prominence, and not the Middle East or Asia? After all, the first civilizations emerged in the Middle East, and China lead the ancient world in technology, and economic and political development, for centuries. We may reasonably wonder, then, why these societies did not extend their dominance around the world, instead of Western Europe.

Diamond addresses this question with considerable clarity in the epilogue to Guns, Germs, and Steel. Here, again, I can only briefly summarize his arguments.

In the case of the Middle East, the answer is that the land is ecologically sensitive; it has low rainfall relative to its primary productivity. Therefore, the region was particularly vulnerable to deforestation, farming, irrigation, and grazing. Precisely because it was inhabited and exploited for so long—longer and more intensively than any other area on earth—it was gradually transformed from the productive forest and grassland that inspired the name Fertile Crescent, into the arid, barren, desert and steppe, that we associate with the Middle East today. Accordingly, the civilizations that developed there were unable to flourish.

In the case of China, the explanation is also related to the environment. Because of its coastline, its islands, its mountains, and its rivers, China remained geographically, and thus economically and politically, unified for over two thousand years. This unity had important consequences for the development of Chinese society. Throughout history, and despite the numerous technologies that developed there, China repeatedly abandoned innovation, and turned its back on the outside world, behavior that would have been impossible in Europe.

The most obvious example, relevant to the themes discussed here, is the fact that, at one time, China supported vast treasure fleets of ocean-going vessels, with thousands of crewmen, who sailed across the Indian ocean, as far as the east coast of Africa. These fleets, presumably, could have reached Europe. However, in the early Fifteenth century, following a power struggle in the Chinese court, the fleets were dismantled, and ocean going voyages were forbidden. Thus, China never expanded its global reach, and remained isolated.

These examples raise another important question; to what extent do culture factors, or individual people, shape human history? This question is related to a great debate, or divide, in history, between those who believe that history can be largely explained by environmental factors, and those who believe that history is better understood as a series of cultural changes, often driven by individual people.

The preceding discussion should make Diamond’s position clear—he believes that history can be largely explained by environmental factors, however, he does acknowledge that local, temporary, conditions, the actions of individuals, and pure, random chance, have potentially large effects. He calls these “wild cards,” and describes how they can and occasionally did change the course of history. He also points out that the key to quantifying the relative effects of these processes is to investigate historical events that can not be explained by the environment. The implication, of course, is that much can be explained by the environment, as his book demonstrates.

I hope this discussion helps clarify the importance of Guns, Germs, and Steel. I think it’s worth mentioning, again, that I have never encountered a satisfactory refutation of his basic theory, nor any reasonable alternative theories. Diamond brings clarity to topics that previously remained obscure, and his work is substantiated by a large body of evidence. Finally, it both supports, and is supported by, our understanding of racial equality.

There is one more point I would like to make before moving on. Confronted by Diamond’s work, many people are tempted to propose a selection mechanism that drove the evolution of fundamental characteristics, such as intelligence, in particular groups of people, especially Western Europeans. The argument is the following: as large societies emerged, people who had particular traits, such as greater intelligence, that allowed them navigate and manipulate the various challenges and opportunities of civilization, were better able to survive, and thus pass on their greater intelligence genes to their offspring, relative to other people who were less intelligent. In this way, large societies provided the selective force that drove an increase in intelligence in particular parts of the world.

At first, this idea seems plausible. Something like this almost certainly occurred during the course of human evolution. Ardipithecus ramidus, one of the first upright walking hominins, who lived about 4.4 million years ago, had an average brain volume of about 350 cubic centimeters, equivalent to that of our closest ancestors, chimpanzees. Over the next 4 million years, hominin brains increased in size dramatically. Homo sapiens, or anatomically modern humans, who appeared about 200,000 years ago, had an average brain size of about 1,350 cubic centimeters, four times the size of chimpanzee brains.

The precise mechanism that drove the rapid expansion of our brains is unknown, although it probably involved cultural or behavioral traits, such as tool use and language. To take the latter example, as language developed, individuals with larger brains, that allowed them to employ language, were better able to survive, and thus pass on their larger brain genes to their offspring, relative to other individuals with smaller brains. Language, therefore, provided the selective force for larger brains, which lead to more sophisticated language, which lead to larger brains, and so on, a positive feedback loop, or co-evolution, that drove the rapid increase in brain size, with corresponding changes in genetic composition and fundamental characteristics.

The problem with applying this logic to large societies is that the time span involved is simply too short. If we assume that the agricultural revolution occurred about 10,000 ya, that the first civilizations emerged about 5,000 ya, and that networks of civilizations of sufficient density and complexity to produce the kinds of changes we are trying to explain emerged in the following one or two thousand years, we are left with a incredibly short period of time, a few thousand years, say, from 3,000 ya to the present, for substantive changes to develop. This is not enough time for natural selection to alter fundamental characteristics. Recall that the expansion of our brains, widely described as an “explosion” in brain volume, occurred over a period of at least 4 million years.

We must therefore return to our previous conclusion; there is no plausible selection mechanism that would have created differences in fundamental characteristics between people around the world including, we can now add, the development of civilizations.